Mississippi Blues Trail Series – Natchez & Ferriday

An Article by Brenda Germany

An Article by Brenda Germany

Photos by Stephen Anderson

It is often said that there are two sides to every story. This is undeniably true of Mississippi’s “Bluff City”, Natchez. The Southland Music Line visited Natchez to explore more of the Mississippi Blues Trail in addition to discovering both sides of the history, sights and, in particular, sounds of this beautiful city. For many, the mention of Natchez brings to mind the refined elegance of lush, azalea-ruffled lawns where stately antebellum homes, reflecting the French and Spanish influences of bygone jurisdictions, sit beneath ancient live oaks. While this sedate vision of Natchez was, in part, and still is accurate today, the “Bluff City’s” history has an intriguingly flamboyant side as well.

Named for the Native American tribe which inhabited the area long before French colonists arrived in 1716 and whose Grand Village and ceremonial mounds still stand within the city limits, the Natchez settlement came to life as an extraordinarily accessible river port at the southern terminus of the Natchez Trace. As early as the 8th century Native American tribes (Natchez, Choctaw and Chickasaw) used and further developed this important passage into an invaluable trade route eventually linking the Mississippi, Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers from Natchez to Nashville. Upon their arrival, the French secured this coveted river port by constructing a fort on the high bluffs above the river, naming it Rosalie in honor of the Countess of Pontchartrain. Natchez’s prosperity quickly grew and at one point claimed to encompass the country’s largest number of millionaires within its boundaries.

Below the bluff, a wide, flat strip of land near the river known as Natchez-Under-the-Hill, the flamboyant side of Natchez’s story, also flourished during this period. Catering largely to boatmen and travelers from the countless flatboats, steamers and cargo ships landing there, as well as local libertines, the growth of saloons, gambling houses and a rowdy nightlife, including music and dance halls, also attracted Natchez Trace highwaymen, river pirates and gamblers, thereby earning it the reputation as the most infamous and dangerous port on the Mississippi River. After years of repeatedly fruitless efforts to tame its notorious character, the January 1836 fire, in which twenty-eight houses burned, and recurrent river flooding reduced Natchez-Under the-Hill to only six original buildings on Silver Street. Today, despite its less than distinguished beginning, tourists now safely explore the remnants of infamous Silver Street and its surviving historic buildings, all of which have been faithfully restored and converted to restaurants, taverns and specialty retail shops.

While much of Natchez-Under-the-Hill’s nightlife and entertainment ceased to exist following the fire, many local musicians who had entertained there began performing at Natchez-Above-the-Bluff clubs, halls and cafes or strolled the streets during the evenings playing their instruments and singing. According to James L. Dickerson, author of the award-winning 2005 book, “The Mojo Triangle: Birthplace of Country, Blues, Jazz and Rock ‘n’ Roll”, these musicians performed a blend of traditional folk music from Europe combined with the exotic rhythms and harmonies of the Choctaw and Chickasaw, and the unique phrasing of slaves from Africa. It was not until the late 1920s, when Jimmie Rodgers began recording what would later be recognized as America’s first country music, that this multi-cultural blend of music took hold. A fiddle tune named “Natchez Under the Hill,” originating along the docks in Natchez, was one of the first original songs ever published (1834) in America, which later became the familiar “Turkey in the Straw.” From that single song began a tradition that would inspire the birth of the Mississippi Delta blues’ rootsy, sparse style and passionate vocals, accompanied on slide guitars. Simply the music of the rural south, in particular the Mississippi Delta, it was performed by both black and white musicians who shared the same repertoire and thought of themselves as “songsters” rather than blues musicians.

Over time Natchez has become heir to many talented and well known musicians such as: Jimmy “Soul Man Lee” Anderson (“I Wanna Boogie”), Glen Ballard (Grammy Award winning “Believe” – Polar Express, co-wrote/co-produced Michael Jackson’s “Thriller” & Alanis Morissette’s “Jagged Little Pill”), Mickey Gilley (17 No.1 country hits, most notably “Stand By Me” from Urban Cowboy), Papa Lightfoot (blues harmonica player, Blues Trail Marker-Natchez), Marie Selika Williams (Coloratura soprano, first black artist to perform for a U.S. president), Geeshie Wiley (country blues singer/guitarist “Skinny Leg Blues”) and most recently Bishop Gunn (rock/blues band –“Natchez” 2018)

The Bluff City’s dedication in preserving the history of its unique musical heritage and contributions to the unfolding of Mississippi’s blues legacy is reflected in the many music festivals and events held in the Miss-Lou District, which it proudly calls home. Comprised of eleven communities surrounding Natchez on the Mississippi side and Ferriday, Jonesville and Vidalia on the Louisiana side, the Mississippi River Bridge unites the shared appreciation held by the “Miss-Lou” for their states’ partnership and contributions to the Birthplace of America’s Music.

One of the most outstanding music celebrations of the many held throughout the year in Natchez, including the Spring Pilgrimage, Natchez Bluff Blues Festival and Great Mississippi River Balloon Race, is the month-long Natchez Festival of Music held each May since 1990. Featuring family friendly entertainment for all musical tastes from classical to rock; the Festival is held at the Natchez Bluffs on South Broadway Street and various other music venues throughout the city.

A recent addition to the Natchez Festival of Music is the Bishop Gunn Crawfish Boil Concert. Native sons of Natchez described as “Torchbearers for a new wave of Blues to come out of the Delta” by Culture Collide, Bishop Gunn organized their 2nd annual concert at the Natchez Bluffs Park overlooking the Mississippi River to bring their fans an exceptional event which included Magnolia Bayou (Gulfport, MS), Black Stone Cherry, Tyler Childers and Bishop Gunn’s own unique fusing of blues, soul and rock excitement. Due to severe weather that evening it was necessary for The Southland Music Line team to leave the concert early to return to the Gulf Coast safely. Those who could remain and brave the storm were rewarded with an outstanding music experience. (The “Line” thanks Sarah Ballenger for her kind hospitality and the assistance extended to us for the event.)

Top photo: A view of Mississippi River in Natchez, MS; above photo: Mississippi Blues Trail marker recognizing Papa Lightfoot & The Natchez Blues

Top photo: A view of Mississippi River in Natchez, MS; above photo: Mississippi Blues Trail marker recognizing Papa Lightfoot & The Natchez Blues

Papa Lightfoot & The Natchez Blues

When arriving in Natchez via Devereaux Drive (Hwy. 61), the first Mississippi Blues Trail Marker is “Papa Lightfoot & The Natchez Blues located at 4 McCabe Street in tranquil Jack Waite Park near the Greater Mt. Sinai Baptist Church.

George “Papa” Lightfoot (March 2, 1924 – November 28, 1971), born Alexander Lightfoot, became one of the most talented American blues singers and harmonica players of the post World War II era. Lightfoot always carried a harmonica in his pocket, and would play at the slightest suggestion. The habit of singing through his harp microphone accounted for his signature rough-hewn vocals, while his harp playing reflected his seemingly unlimited imagination. Lightfoot recorded several sessions in his late twenties: Peacock Records in 1949 (unfortunately, never issued), Sultan Records (the first Mississippi based label reported by the national music press) in 1950, Aladdin Records in 1952, and Imperial Records in 1954. After singles for Savoy Records in 1955 and Excello Records in 1956, Lightfoot stopped recording.

As interest in Delta blues grew during the 1960s, Lightfoot’s name became well known and, in 1969, record producer Steve LaVere persuaded Lightfoot to record again. The result of their collaboration was the album “Natchez Trace”, released on Vault Records in 1969, which brought Lightfoot briefly to the forefront of the blues revival. “Rural Blues Vol. 2” followed on Liberty Records later that same year. However, his comeback was cut short by his untimely death in late 1971 of respiratory failure. These final recordings were reissued in 1995 as “Goin’ Back to the Natchez Trace”, with six additional tracks and recorded monologue.

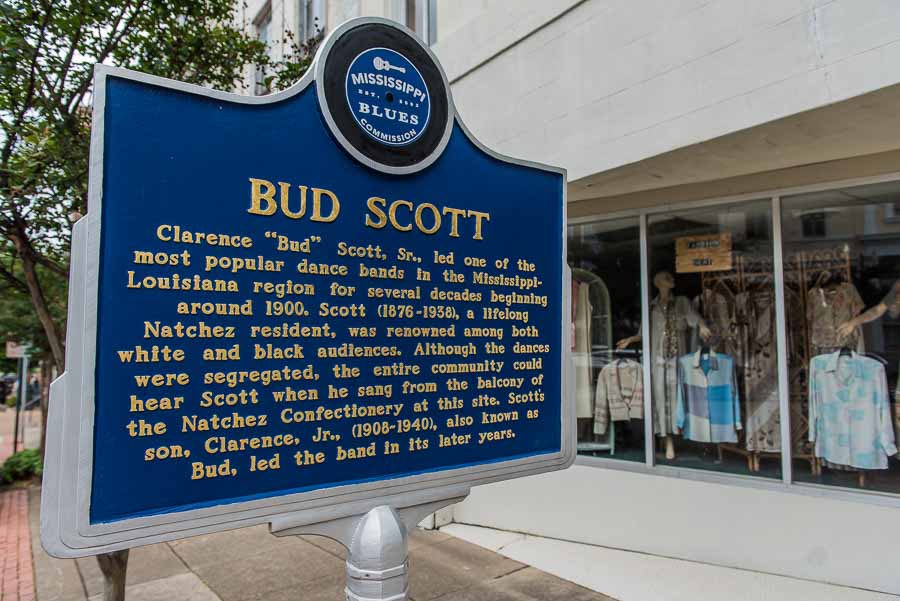

Above photo: Mississippi Blues Trail marker recognizing Bud Scott in Natchez, MS.

Above photo: Mississippi Blues Trail marker recognizing Bud Scott in Natchez, MS.

Bud Scott

In an article written for the Natchez Times newspaper around 1940, several years after Scott’s death in 1938, Edgar Simmons Jr. wrote of Scott, “Bud Scott was a product of the sweat-drenched Dixie river towns, and jazz flowed out of his mouth and fingers, out of every wide pore of him, like honey out of a barrel. Bud sang on the galleried second story of the Natchez Confectionary on summer nights with a megaphone that his ham-like hand nearly swallowed. The gallery seemed to hang in the night sky and it dripped with the evening dew.”

The marker commemorating Clarence “Bud” Scott’s life (1876-1938) and contributions to the development of blues, ragtime and jazz stands at 409 Main Street in downtown Natchez adjacent to the only remaining balconied store front and what is believed to be the former Natchez Confectionary from which he serenaded admiring audiences. Known as the “Professor” for his respected position among the era’s orchestra leaders, Bud Scott achieved wide acclaim in the early twentieth century, playing for three U. S. presidents. His stature was achieved strictly through his legendary live performances; he apparently never made a record or published his songs. Scott continued to perform until unable to sing in his final years. Bud, Jr. and the band continued to play following Scott’s death. Scott’s home stands today at 1011 North Union Street in Natchez.

Above photo: Mississippi Blues Trail marker recognizing one of the deadliest and most devastating fires in American history.

Above photo: Mississippi Blues Trail marker recognizing one of the deadliest and most devastating fires in American history.

Natchez Burning

On the night of April 23, 1940 one of the deadliest and most devastating fires in American history took the lives of over 200 people at the Natchez Rhythm Club. The Blues Trail marker memorializing the incident is located at 301 Main Street, near the Natchez Museum of African American Culture.

The dance hall where the Rhythm Club stood was a steel-clad wood-frame building at 1 Catherine Street, just blocks from the city’s business district. The former blacksmith shop, once used as a church, was 120 ft x 38 ft with 24 windows that were mostly shuttered or nailed shut at the time of the fire to prevent gatecrashers. Though young and old throughout the city had to save for months to pay the 50 cent entrance price, when the evening arrived the dance hall quickly filled with hundreds beyond expectation.

As members of the local Moneywasters Social Club were enjoying the song “Clarinet Lullaby”, performed by the much anticipated Walter Barnes and His Royal Creolians orchestra from Chicago, the blaze reportedly began at 11:30 pm. A discarded match or cigarette ignited the spanish moss that had been sprayed with FLIT, a petroleum-based insecticide, hanging from the ceiling of the Rhythm Club as decoration for the special evening. When the flames erupted, hundreds of frantic patrons stormed the only door. It was estimated that, sadly, only 150 of the large crowd in attendance escaped. The fire consumed the interior within 15 minutes and the entire building was destroyed within an hour. Bandleader Walter Barnes, a Vicksburg native, was hailed as a hero for trying to calm the crowd while he and the band continued to play the song “Marie.” Fellow bandleader Clarence “Bud” Scott, Jr., Barnes’s guest, also perished in the flames.

The outpouring of heartbreak and emotion felt for the disaster was memorialized in songs such as “The Death of Walter Barnes”, by Leonard Caston; “The Natchez Burnin”, by Howlin’ Wolf and “Natchez Fire”, by John Lee Hooker. Soon afterward a memorial marker was erected in Natchez’s Bluff Park and in 2010 the Rhythm Club Museum opened at the former site of the club on Catherine Street.

As is so often the case, awakenings are born of tragedy. Following the event, cities across the country passed new fire safety laws prohibiting the overcrowding of buildings and aimed at making public buildings, especially nightclubs, safer.

Above photo: Mississippi Blues Trail marker recognizing the Ealey Brothers.

Above photo: Mississippi Blues Trail marker recognizing the Ealey Brothers.

Ealey Brothers

The marker recognizing the Ealey Brothers of Sibley, MS is located in the Natchez Bluff Park on South Broadway Street near the famed Natchez Gazebo. David “Bubba”, Y Z, Melwin and Theodis Ealey were among the most prolifically talented musicians in the Natchez area, excelling as members of their own bands and as individual performers.

David “Bubba”, eldest of the four brothers, began playing guitar locally in his teens and soon moved to New Orleans where he played at house parties along with Guitar Slim in the style similar to Lightnin’ Hopkins and Little Son Jackson. After living in Oakland, CA for many years, he retired to Port Hudson, LA continuing to perform informally.

Recently presented with the 2019 Jus’ Blues “The Muddy” Lifetime Blues Award, Y Z Ealey first began playing guitar as a child, imitating his older brother, “Bubba”. While living in Oakland following his service in the Navy, Y Z performed with artists such as Big Mama Thornton of “Hound Dog” fame, and fondly recalls the music of local steel guitarist L.C. “Good Rockin’” Robinson. Upon Ealey’s return to Natchez in 1959 he billed himself as Y Z “Good Rockin’” Ealey in tribute to Robinson. Y Z formed The Merrymakers band in 1960 with his younger brothers plus Tobe Smith, Jonathan Grennell and A. J. Reed to perform in the Natchez area. The band also served as the house band at Haney’s Big House in Ferriday, LA for many years.

Several years after joining his brothers to play in Y Z’s and The Merrymakers in the Natchez area, Melwin also moved to Oakland, CA performing rhythm and blues, country music and ballads for decades at local venues.

Theodis, who earned the name of “The Bluesman Lover” for his often risqué love songs also learned to play the guitar at an early age from an older brother, Y Z. By age thirteen Theodis was playing bass in Y Z and The Merrymakers, which debuted in Natchez at the Horseshoe Circle nightclub. He also played guitar with such notable artists as Little Milton, Johnny Clyde Copeland, the Blues Brothers and the legendary Charles Brown. Theodis’ most recent awards include the 2007 Jus’ Blues Best Blues & Soul Man Song of the Year for “Francine” and the Jus’ Blues Lowell Folsom Legends Award for 2006 and 2008.

The Delta Music Museum of Ferriday, Louisiana honored the four Ealey Brothers with induction into the museum’s Hall of Fame June 10, 2017 and a jam session at the adjacent historic Arcade Theater following the ceremony.

Above photo: Mississippi Blues Trail marker recognizing the music of Ferriday, LA.

Above photo: Mississippi Blues Trail marker recognizing the music of Ferriday, LA.

Mississippi to Louisiana – Ferriday

A short drive across the Mississippi River Bridge lays Ferriday, Louisiana, a “Miss-Lou” community, which has partnered for many years with Natchez in the promotion of blues, jazz and rock and roll music. Ferriday claims to have produced more famous people per square mile than any other city in America including such recognizable names as: Mickey Gilley (country musician and owner of Gilley’s Nightclub in Pasadena, Texas), Jerry Lee Lewis (famed rock and roll singer/pianist), Howard K. Smith (CBS and ABC commentator and anchorman), Jimmy Lee Swaggart (evangelist) and Leon “Pee Wee” Whittaker (blues trombonist).

The Mississippi Blues Trail marker commemorating Ferriday’s contribution to the blues through Haney’s Big House is located on the grounds of the Delta Music Museum at 218 Louisiana Avenue in the downtown historical district. Housed in the historic former post office, the museum features sixteen exhibits of rock and roll and blues musicians from the Mississippi Delta. Most prominent among the museum’s exhibits is a sculpture of the three Ferriday cousins: singers, Mickey Gilley and Jerry Lee Lewis and evangelist, Jimmy Lee Swaggart, at the piano.

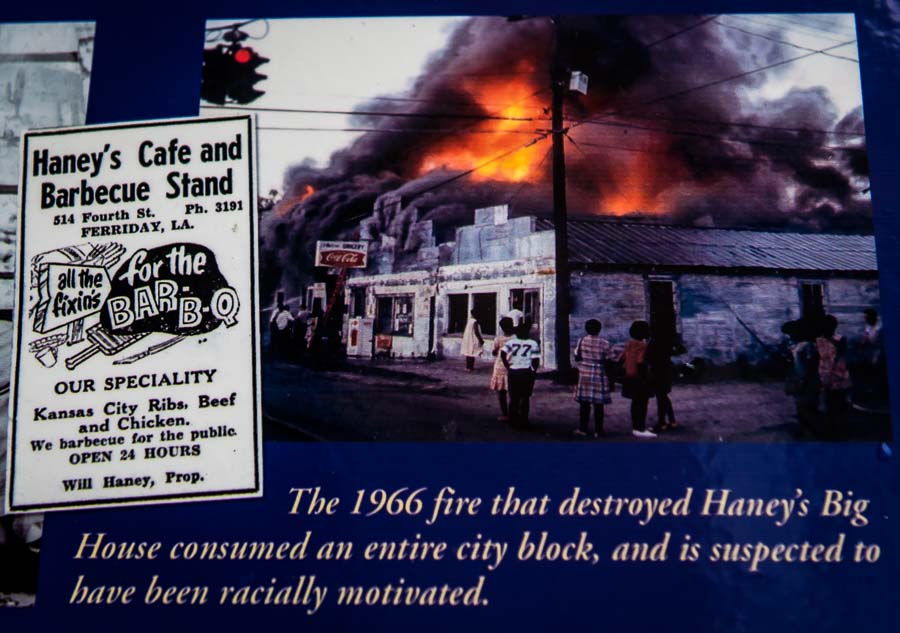

Above photo: Mississippi Blues Trail marker photo recognizing Haney’s Big House in Ferriday, LA.

Above photo: Mississippi Blues Trail marker photo recognizing Haney’s Big House in Ferriday, LA.

Will Haney was one of Ferriday’s leading African-American businessmen. But, he was nationally known for his famous cafe and nightclub located in the 500 block of 4th Street (now East Wallace Blvd.) in Ferriday. Operating at its peak from 1940 through 1966, the venue began as a 24 hour barbecue restaurant later expanding to include gambling and music. Haney’s Big House, as it was known after Haney enlarged the cafe, became a stopping point on the famous Chittlin’ Circuit, attracting such entertainers as: Ray Charles, B.B. King, Fats Domino, Irma Thomas and many others. During his youth, Jerry Lee Lewis would stand at the back door with trombonist Pee Wee Whittaker listening to the rhythm and blues. Lewis once confided to Whittaker that Haney’s was the first place he heard rock and roll music played.

Trombonist Leon “Pee Wee” Whittaker, of Newellton, LA, led a house band at the club for many years and also performed with the Rabbit Foot Minstrels of Port Gibson, Mississippi. House bands were also led by Natchez entertainers Y Z Ealey and Hezekiah Early, who had previously played the club with Natchez guitarist John Fitzgerald and singer Elmo Williams. Whittaker later played in Early’s band, Hezekiah and the Houserockers, for almost to 30 years.

In the 1950s, when Ferriday was “wide open” for gambling and entertainment, 300 to 400 people would be inside and spilling out onto the streets. Haney’s nightclub operated until 1966 when the building was destroyed by a fire attributed to a faulty ice machine. No one was injured in the blaze; however, it destroyed most of the structures on the block. As the incredible musical influence of Louisiana and Mississippi is well documented, it is not surprising that the neighboring cities of Natchez and Ferriday had an abundant musical exchange over the years and will likely continue to do so.

There are currently over 200 Mississippi Blues Trail Markers, with more being added regularly. We invite you to continue to follow along with The Southland Music Line team as we seek out more of the fascinating stories about Mississippi, the birthplace of America’s music.

Click Here for more articles in the Mississippi Blues Trail Series at The Southland Music Line.

Click Here for more articles in the Mississippi Blues Trail Series at The Southland Music Line.

Credits:

Mississippi Blues Trail and Mississippi Blues Commission

Rosaliemansion.com

https://www.onlyinyourstate.com/mississippi/historic-natchez-under-the-hill-in-ms/ ,by Daniella DiRienzo Sep. 30, 2016

https://mississippiencyclopedia.org/entries/natchez-under-the-hill/ by Jaime Elizabeth Boler, Jones County Junior College

Natchez Under-the-Hill and Silver Street, by Ellen Pack, 2000

The Delta Democrat-Times, Greenville Mississippi, by James Marlow, Apr 24, 1940

https://www.theodisealey.com/about/

“Mojo Triangle: Birthplace of Country, Blues, Jazz and Rock ‘n’ Roll”, by James L. Dickerson, 2005

“Cold Case: Haney’s Big House-a legendary place-down the street from Morris’ shop”, Concordia Sentinel, by Stanley Nelson, Nov 26, 2007

“Cold Case: Half-century old photos show capture Will Haney inside his famous Ferriday club”, Concordia Sentinel, by Stanley Nelson, Dec 8, 2010

Page Designed & Edited by Johnny Cole

© The Southland Music Line. 2019. All rights reserved